Sequence Parallelism for Inference: Part 1

Introduction

Nd+ parallelism techniques are often invented for training first, then adapted for inference. Most techniques have seen great success in today’s inference world (both individually and together). However, Sequence Parallelism has not seen wide adoption in the open source world. If you look at vLLM or SGLang today, sequence parallelism is either in not-so-active development or completely deprioritized.

As a huge fan of low time-to-first-token (TTFT) long-sequence inference (motivated by my work at Augment Code—check us out!), this greatly saddens me. This blog series aims to bring back some love for Sequence Parallelism for Inference.

💔 Another embarrassing reason for this blog series is because I have spent ungodly hours re-inventing Sequence Parallelism variants and begrudgingly realized that many of my so-called original ideas were just from papers I read back in school (many such cases). So I decided to sit down and write to prevent another poor soul (and my future self) from wasting time re-deriving the basics of Sequence Parallelism

This blog series solely focus on prefill time-to-first-token. If you care about memory overhead (weight + KV cache) or decode time-per-output-token then consider using Sequece Parallelism in conjunction with other techniques like other parallelisms, quantization, prefill-decode disaggregation, page/radix attention, etc.

Notation

$N$ is the tensor size

$p$ is the number of devices

$B$ is batch size

$T$ is sequence length

$nkv \text{ and } nq$ denote number of kv heads and q heads respectively.

$d$ is headdim

$H$ is hidden dimension, $H = nq \times d$

$\ll$ means order of magnitude smaller

What is Sequence Parallelism (SP)?

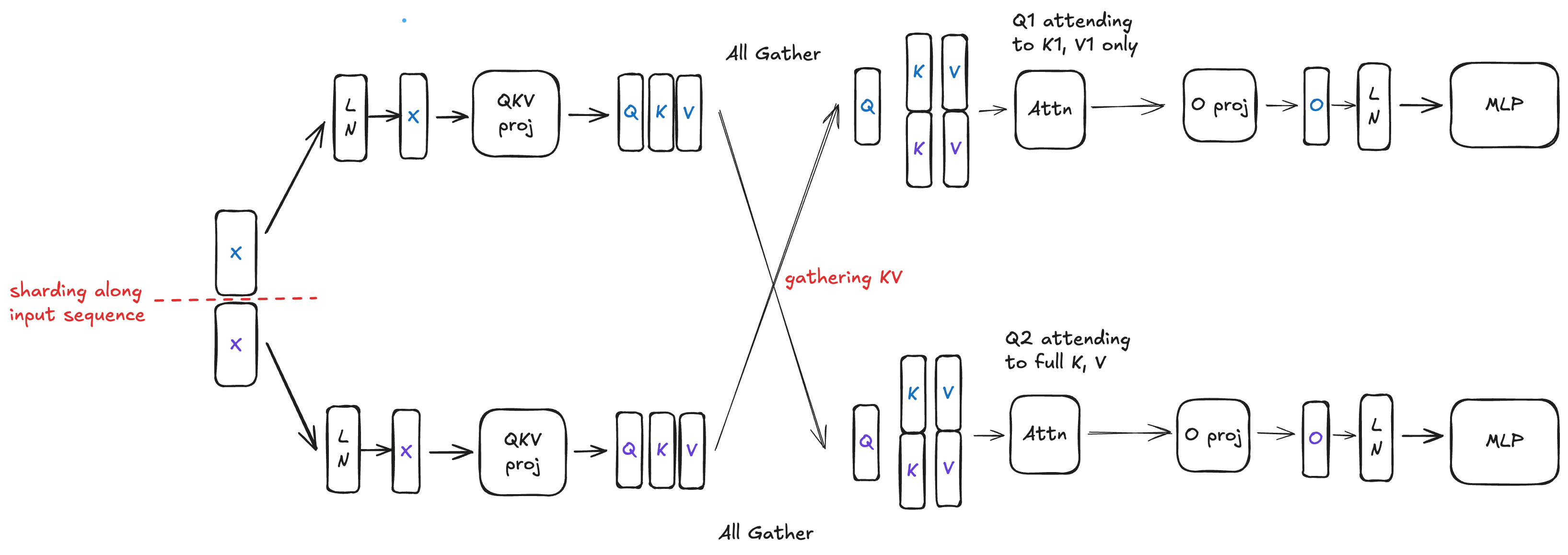

In one sentence: sequence parallelism shards the input along the sequence dimension across devices, and subsequent operations—such as ResidualAdd, LayerNorm, and MatMuls—are performed on these partitioned sequences. Attention is the only exception, where tokens are dependent (causal) and often require either full KV and/or full Q for computation.

The idea sounds simple enough, but in reality there are many sequence parallelism variants. Before we dive deeper into different SP variants, let’s take a quick detour to explain why Tensor Parallelism isn’t good enough for low-latency prefill.

Why is Tensor Parallelism (TP) not good enough?

To reduce TTFT, the first thought is to apply a higher degree of TP. During prefill, as we increase TP degree, both attention computation and MLP scale down roughly linearly. However:

- LayerNorm computation does not scale with more devices

- LN is a point-wise operation on input activation, which is not sharded during TP. Moreover, when we say LN scales, it’s not computation that scales but rather memory I/O. Point-wise operations are more memory bandwidth-bounded than compute-bounded. Shorter sequence length means less I/O during LN

- All-Reduce communication volume increases with more devices

- For ring-based All-Reduce, the per-device communication volume is $\frac{2 \times (p - 1) \times N }{p}$. As TP degree grows, this volume increases by 1x (TP=2), 1.5x (TP=4), and 1.75x (TP=8)

- Furthermore, we have to do 2 All-Reduces during TP, one after output projection (O proj) and another after ffn2 (or shrink), both of which have $N = B \times T \times H$

For latency-sensitive applications, this is simply not good enough. The solution is, as you’ve guessed from the title, Sequence Parallelism (and friends)!

Sequence Parallelism variants

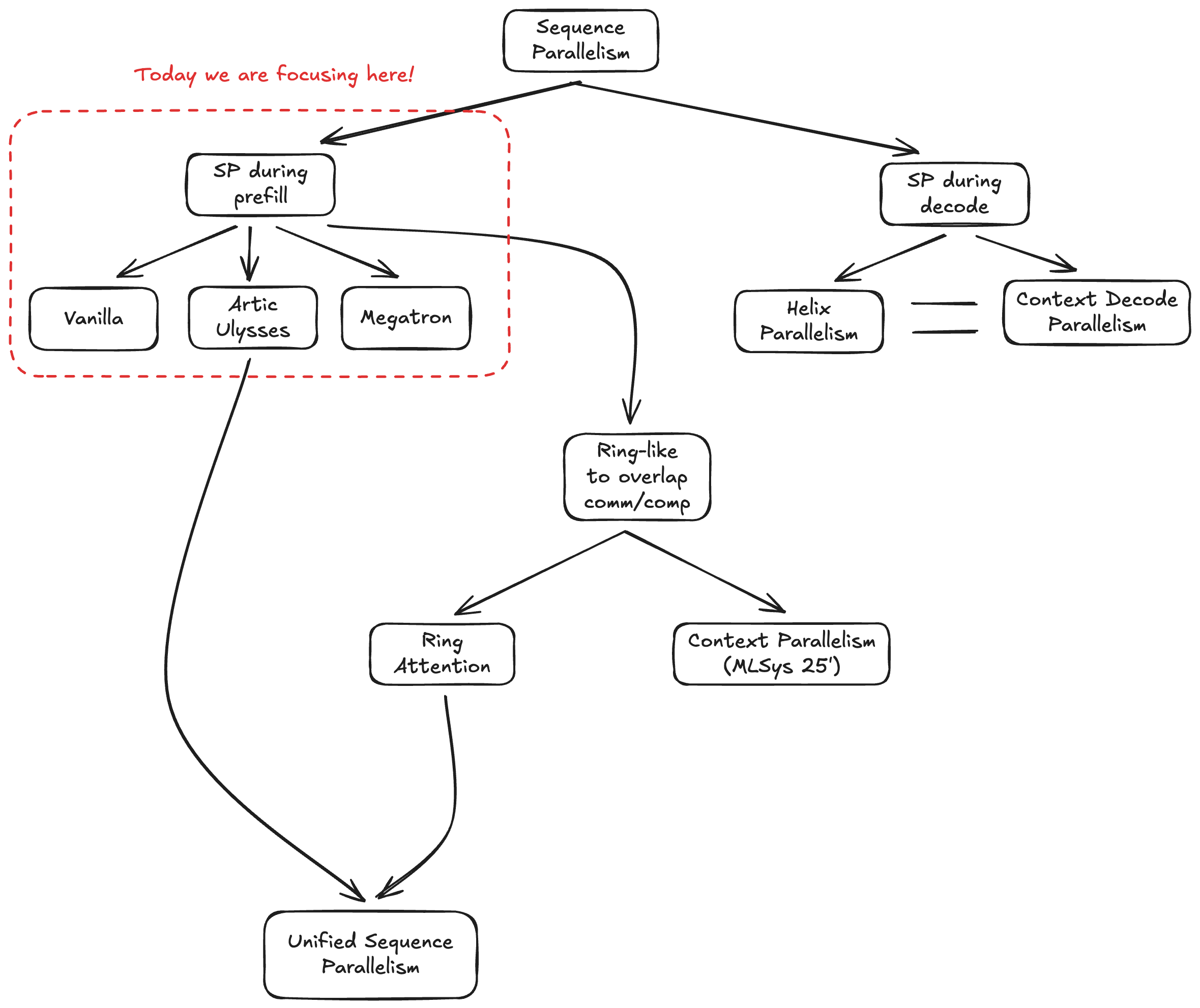

There are many SP variants. I’ve created this semi-opinionated taxonomy to organize them.

As shown in the taxonomy, we’ll focus on Vanilla SP, Megatron-style SP, and Ulysses SP.

As shown in the taxonomy, we’ll focus on Vanilla SP, Megatron-style SP, and Ulysses SP.

Vanilla Sequence Parallelism (or Context Parallelism)

Pros: With Vanilla Sequence Parallelism, MLP and LN scale down roughly linearly with the number of devices since these operations now act on sharded input sequences.

Furthermore, the communication overhead is significantly lower than TP:

Pros: With Vanilla Sequence Parallelism, MLP and LN scale down roughly linearly with the number of devices since these operations now act on sharded input sequences.

Furthermore, the communication overhead is significantly lower than TP:

We only need 1 All-Gather compared to 2 All-Reduces

For Ring All-Gather, the per-device communication volume is $\frac{(p - 1) \times N }{p}$

In this case, $N = B \times T \times 2nkv \times d$. For GQA, $nkv \times d \ll H = nq \times d$

Cons: Vanilla Sequence Parallelism introduces attention computation imbalance. The rightmost portion of Q must attend to all of KV, while the leftmost portion of Q only attends to its corresponding leftmost portion of KV. As a result, Attention still scales with more devices but performs slightly worse than TP.

You can use load balancing algorithms to combat the attention imbalance. For strictly causal masks, one notable approach is zig-zag attention.

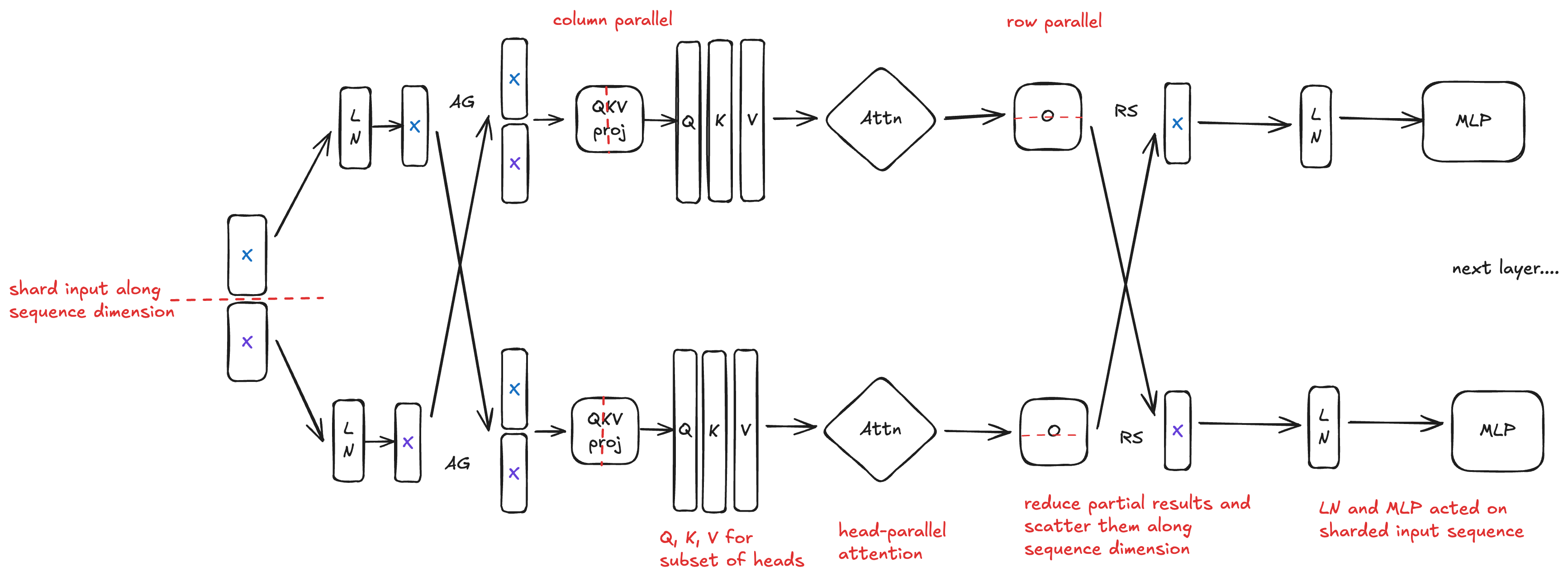

Megatron Sequence Parallelism

The high-level idea: perform Attention and MLP blocks in TP, and LayerNorm in SP. In detail:

The high-level idea: perform Attention and MLP blocks in TP, and LayerNorm in SP. In detail:

Shard the input sequence along the sequence dimension

Attention LayerNorm acts on the sharded input sequence

All-Gather the sharded input sequence into the full sequence

Perform the Attention Block (QKV proj, Attention, and O proj) in traditional TP fashion

Reduce partial results of O proj and scatter them along the input sequence

MLP LayerNorm acts on the sharded input sequence

All-Gather the sharded input sequence into the full sequence

Perform the MLP Block (expand, activation, and shrink) in traditional TP fashion

Reduce partial results of shrink and scatter them along the input sequence for the next layer’s Attention LayerNorm

❓ Uhh why would one use this over TP? Isn’t the point of Megatron-SP is to reduce activation memory overhead during training?

Yes, but surprisingly this is faster than TP for prefill. While the communication overhead is roughly the same—All-Reduce is equivalent to All-Gather + Reduce-Scatter (relatively true for large message sizes, assuming the same tensor size)—LN scales linearly since it acts on sharded input sequences.

Ring All-Gather and Reduce-Scatter both have per-device communication volume of $\frac{(p - 1) \times N}{p}$. In practice, Reduce-Scatter is usually slightly slower than All-Gather.

As noted earlier, ring All-Reduce per-device communication volume is $\frac{2 \times (p - 1) \times N}{p}$, which is exactly All-Gather + Reduce-Scatter. In practice, ring All-Reduce for large message sizes is often implemented as a two-phase algorithm: Reduce-Scatter followed by All-Gather.

Since we don’t care about reducing activation memory, we can do even better for inference by eliminating one pair of All-Gather + Reduce-Scatter.

Instead of All-Gathering the sharded sequence after MLP-LN, we skip it and perform the MLP block on the sharded sequence. This eliminates a pair of All-Gather + Reduce-Scatter, cutting our communication overhead in half.

Instead of All-Gathering the sharded sequence after MLP-LN, we skip it and perform the MLP block on the sharded sequence. This eliminates a pair of All-Gather + Reduce-Scatter, cutting our communication overhead in half.

Pros: MLP, LN, and Attention all scale down ~linearly with the number of devices. Attention is head-parallel (no imbalance), while MLP and LN act on sharded input sequences. The communication overhead is ~1/2 that of TP—we only do one All-Gather + Reduce-Scatter compared to two All-Reduces.

Cons: Compared to Vanilla SP, Megatron SP has significantly higher communication volume

For the Megatron variant above, we do an All-Gather after Attn LN and a Reduce-Scatter after O proj, both with tensor sizes of $N = B \times T \times H$.

Once again, because $nq >> nkv$ for GQA models, per device communication volume of Megatron SP is significantly higher than that of Vanilla SP.

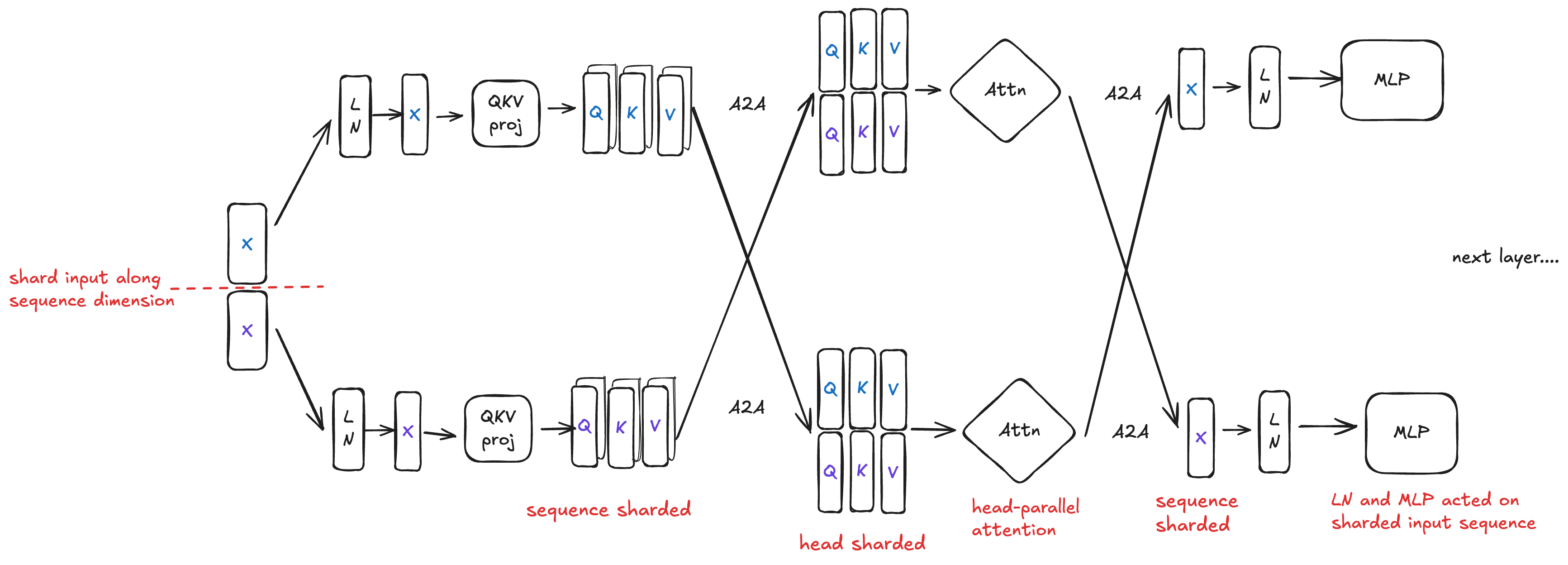

Ulysses Sequence Parallelism

The high-level idea: perform only Attention computation in TP and everything else in SP. In detail:

The high-level idea: perform only Attention computation in TP and everything else in SP. In detail:

Shard the input sequence along the sequence dimension

Attention LayerNorm acts on the sharded input sequence

Pass the sharded input sequence to QKV proj to get sequence-sharded Q, K, V

Perform an All-To-All to reshard the sequence-sharded Q, K, V into head-sharded Q, K, V

Each device performs attention on a subset of heads

Perform an All-To-All to reshard the head-sharded

attn_outputback to sequence-shardedPass the sequence-sharded output to O proj, LayerNorm, and MLP block

Pros: MLP, LN, and Attention all scale linearly with the number of devices since Attention is head-parallel (no imbalance). The communication overhead is significantly smaller than TP—two All-To-Alls during Ulysses SP compared to two All-Reduces during TP.

The per-device All-To-All communication volume is $N$. In practice, the self-data transfer step (where a device sends $\frac{N}{p}$ data to itself) is very fast because it’s just a local copy.

For Ulysses, we perform an All-To-All after QKV projection where $N = \frac{B \times T \times (nq + nkv) \times d}{p}$ and another All-To-All where $N = \frac{B \times T \times H}{p}$.

Notice that per-device communication volume scales down roughly linearly with more devices. At $p = 4$, the ratio between Ulysses SP and TP is $\frac{2nq + nkv}{12nq}$. For GQA where $nkv \ll nq$, this ratio is much smaller than 1!

Cons: Ulysses cannot shard the sequence dimension beyond the number of KV heads, which is a deal breaker for MHA models where $nkv = 1$ or for GQA models where $nkv$ is substantially small. Ulysses has slightly higher communication overhead than Vanilla SP.

- The per-device communication volume ratio between Ulysses and Vanilla SP is $\frac{2nq + nkv}{8nkv}$. For GQA with small $nq / nkv$, this ratio is only slightly larger than 1!

Some closing notes

So far, it’s been really fun to see how you can move communication between Transformer ops, switch between different sharding strategies, and shave off communication overhead. The computation and communication nature then change drastically. Notice how in all of these sequence parallelism variants, communication and computation are still done separately, the next post will be about fusing and overlapping them together! Stay tuned.